Genome editing in humans

A survey of law, regulation and governance principles

This study of the Scientific Foresight Unit (STOA) of the European Parliament provides an overview of human genome-editing applications and a review of the principles that guide the governance of genome editing in humans, at EU level and worldwide. The study also formulates a series of policy options targeted at basic research and clinical applications, both somatic and germline.

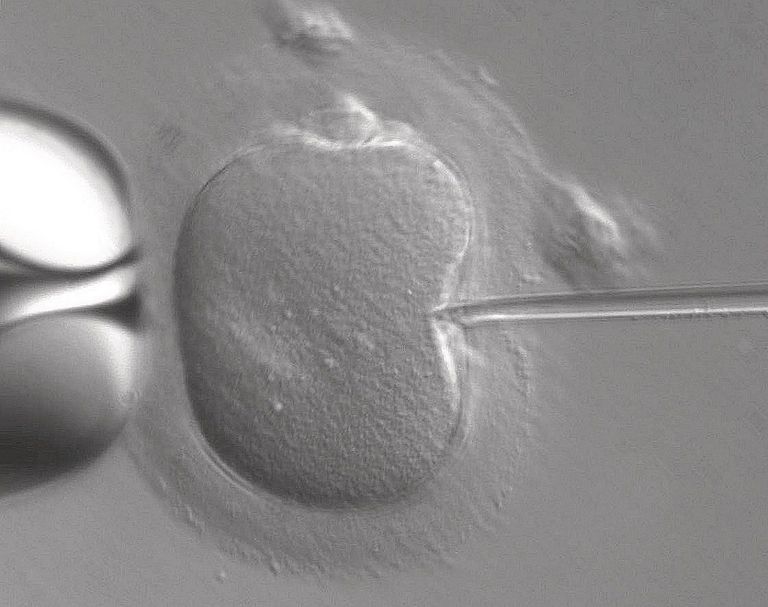

Genome editing is a powerful new tool allowing precise alterations in the genome. The development of new approaches based on the CRISPR-Cas9 system has made this process much more efficient, flexible and affordable, relative to previous strategies.

These technological advances originated in remarkable interest in possible applications, both in fundamental research and in the treatment or prevention of disease and disability. Possibilities range from restoring normal function in diseased organs by editing somatic cells to preventing genetic diseases in future children and their descendants by editing the human germline.

As with other medical breakthroughs, each such application comes with its own set of risks, benefits, ethical issues and societal implications, which may require the revision of existing regulatory frameworks. Important questions raised include how to balance potential benefits against unintended harms, how to govern the use of these technologies, how to incorporate societal values into relevant clinical and policy applications, and how to respect the inevitable cultural specificities that shape the future direction of the use of these technologies.

The goal of this study was therefore to provide an overview of the state-of-the-art of the science, as well as an analysis of current and projected regulatory, ethical, legal and social implications. Based on these findings, policy options were provided.

The internal market for health and 'wellness' services and products can and is already subject to considerable harmonisation in the European Union. Provided that there is sufficient consensus, there is ample room to either introduce genome editing-related provisions in existing directives and regulations (vertical approach), or to enact specific genome-editing legislation (horizontal approach). Besides legislative intervention, it is also possible to explore alternative or cumulative public and private governance mechanisms.

Harmonised definitions would be beneficial to the internal market for health and wellness services and products. These facilitate legal certainty in the internal market, improving the prospects for citizens (as patients and consumers), companies and healthcare providers (public or private) to navigate the different national rules and a fragmented legal landscape. Uniform definitions facilitate comparison and organic approximation of national legislation, policies, and governance structures.

Legal definitions should include appropriate resilience mechanisms to ensure sustained correspondence with scientific knowledge. From a regulatory perspective, the use of qualifiers such as 'somatic versus germline', 'hereditable' genome editing, or 'modifying genetic identity', is considered scientifically outdated, vague and prone to differing legal interpretations. Somatic as well as germline applications may carry associated dangers. Once clinical safety is established, germline interventions could also have strong therapeutic potential. Possible horizontal harmonisation approaches could include, for example, maintaining a general prohibition, in which the clinical risk-benefit ratio is unacceptable and, additionally, clarifying concepts and, most importantly, creating exceptions for research and future treatments of serious diseases.

Regarding genetic eugenics prohibited by Article 3 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, this study proposes the option of regulation to expressly clarify or extend the prohibition to the actions of private actors and to somatic interventions where these cannot be considered to be the result of informed and free consent, and simultaneously clearly exempting preventive and precision medicine.

Regarding advanced therapeutic product regulation, genome-editing products are currently subject to a centralised approval procedure, but exceptions are decided locally. One option would be to further harmonise exceptions granting patients early access, e.g. compassionate use, named- patient use and hospital exceptions.

As for genome editing in assisted reproduction techniques, rules and proposals to allow editing are often linked with the treatment of serious diseases. There is an urgent need to define and, if possible harmonise science-based criteria used to determine the seriousness of a given disease, including both from a patient-centric perspective and using medical diagnosis elements.

Uncontrolled somatic editing can pose great social and ethical risks (e.g., inequality, public health problems, interventions in children and people unable to consent, discrimination, etc.). Regarding wellness and cosmetic somatic editing (including enhancement), strict regulatory framework for market approval only applies to products used for the treatment, prevention or diagnosis of a disease. The use of 'human enhancement' as a criterion for unacceptable interventions is not useful, as it is too vague, value-charged and difficult to enforce. An option would be to ensure public health prevention by determining types of editing that should be prohibited or restricted, practitioners' professional qualifications, safety and technical requirements. Also here, a multi-level, risk-based approach would allow specific rules to be defined for prohibited and high-risk genome-editing interventions. Possible criteria could include the objectives of the intervention, expected outcomes and levels of risk for individuals and society.

Regarding medical/reproductive travel and beauty/wellness tourism, some countries have more permissive legislation or lack the ability to enforce rules. Restrictions should not hamper access to experimental or recently approved therapeutic options, including the participation in clinical trials. Possible options include the extraterritorial application of EU and Member State law to procedures performed abroad (provided that fundamental rights and freedoms are respected).

As for enforcement and forensic activities, the enforcement of prohibitions needs to account for fundamental rights and freedoms. An option would be to balance the needs for prevention and reintegration relating to the specific illicit conduct with the legal rights, interest and well-being of the victim. Secondly, subjects of illicit genome editing could be treated as victims and could be specifically allowed to refuse privacy or forensic activities invasive to their physical integrity. The long-term monitoring and inclusion in registries must also respect the rights to privacy, family life, personal integrity and autonomy.

Counterfeited or falsified services and products are a known intellectual property rights (IPR) and a public health issue. Genome editing could be included in the sphere of measures included when tackling this problem. Private governance through technology-licensing agreements already plays an important governance role. This study identifies an option to develop general guidance or model clauses for ethical licensing. The use of artificial intelligence (AI) systems for genome editing is a future area of concern and should be the object of consideration in AI-related regulation.

In conclusion, this study shows that while genome editing is the source of great expectations for the medical field, several ethical, social and legal questions remain to be addressed. Regulatory and governance mechanisms are greatly needed in the EU.

Standard-Nummer: ISBN: 978-92-846-9455-6